Guilt, Conflict and the Drama Triangle of Persecutor, Rescuer and Victim

Most of us are familiar with guilt; be it through a feeling of wrongdoing, or as a driver for something we ‘ought’ to do. When either of these experiences takes hold the result is a cocktail of resentment, blame and power struggles.

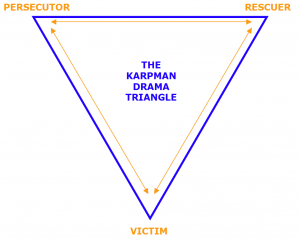

If our reaction is to: attack, or rescue and placate, or take the position of the underdog, then we are in the Drama Triangle of Persecutor, Rescuer and Victim. As the drama unfolds we can swap these three roles fluidly, especially when guilt is involved.

So how does this play out and how can it be stopped?

Defining guilt:

Guilt is an emotion based on real or perceived wrongdoing, determined by our values, or established laws and procedures. We internalize it through our thoughts and self-esteem, and act it out through our body language, words, tone and behaviour.

Guilt can be healthy and appropriate, or toxic and debilitating:

- It is healthy and appropriate when our morals inform us that we’ve done something wrong, and we then find a way of making it right.

- It is toxic when we apologise excessively, get stuck in a sense of wrongdoing and find it hard to forgive ourselves. Debilitating guilt stems from and feeds shame, and has its roots in fear.

While guilt and shame may trigger one another, they are different feelings:

- Guilt is focused on our behaviour: “I did a bad thing”

- Shame turns that sense of wrongdoing inwards: “I am a bad person”

Wanting to avoid guilt, shame and blame triggers the Drama Triangle, which exacerbates them all.

Defining the ‘Drama Triangle’:

Karpman’s model describes the dynamic between two or more people who act out the behavioral roles of ‘Persecutor’, ‘Rescuer’ and ‘Victim’. While these positions change during the drama, we all have a leading ‘go-to’ role learned in childhood.

As a result we may tend to:

- Attack or accuse, take a superior position, make demands (Persecutor)

- Offer assistance, whether sought or not, to validate our good nature and see others in need of our help (Rescuer)

- Feel helpless, an underdog and in need of external help (Victim)

Although the Persecutor and the Rescuer are seen to have more power, each role has low self-esteem at its basis. Consequently, all have their costs and benefits and a certain amount of leverage.

“Play it again Sam!”

Our go-to characters can eventually become attitudes in life and the masks we wear for self-protection. As we operate from these positions, we unconsciously attract those in the opposite role who will help us perpetuate the drama.

Consequently, a Persecutor and Victim will find each other, as will a Rescuer and Victim. This repetition reaffirms our core assumptions and recreates familiar dynamics with those we meet.

It is because self-esteem is at the root of this drama, that guilt is such a strong trigger for an easy costume-change in the Drama Triangle.

Theatre of the absurd? The Drama Triangle in action:

When these roles are the masks we put on and take off, we become the ventriloquists of their scripts and actions. In time we play them with ease, and even unconsciously, so that stepping into these can become second nature.

An example of how fluidly we change roles:

- Someone in Persecutor role accuses another who goes into Victim.

- The Persecutor may feel guilt for their behaviour and Rescue them, or

- Continue to attack the Victim, who looks for a Rescuer elsewhere.

- This third person may attack the Persecutor who then goes into Victim.

- The Rescuer is now the new Persecutor, the original Persecutor the new Victim and the original Victim the possible Rescuer.

Victims can also turn into Persecutors if they retaliate, or turn on their Rescuer for meddling or ‘nagging’. Equally, a Rescuer can become Persecutor to the ‘Victim’ for not acting on their advice.

When blame is involved, one person may persecute and the other deflects guilt with a justification (Victim). The latter may then vent to another (Rescuer), who may or may not get involved.

In all these examples the triangle perpetuates guilt, blame, resentment and a power imbalance.

Four common examples of relational guilt that trigger the Drama Triangle:

The drama often starts and roles change when:

- Guilt is passed back and forth in a Ping-Pong of blame

- We feel guilty about what we’ve said and how we’ve said it

- We feel guilty about what we’ve done

- We feel guilty for saying ‘no’ to someone

Guilt and blame often go hand in hand. Like blame, guilt too can be dualistic in nature: someone or something is either right or wrong, good or bad, acceptable or not. By engaging in it in such win-lose terms, we also give rise to resentment, blame and power imbalances. Winning then becomes a battle of wills and wits, which results in roles changing swiftly and easily.

While some imbalances are circumstantial, for instance with a boss, parent or teacher, others are created. Moreover, if we are apprehensive about turning down a request out of a sense of duty, we are engaging in toxic guilt. This can in turn trigger the Drama Triangle through our communication if we become: aggressive (Persecutor), or passive-aggressive (resentful Rescuer), or passive (justifying Victim).

So how do we stop this drama and guilt?

We move away from all or nothing thinking towards discernment and learning.

- Differentiate between guilt (action) and shame (self): Making mistakes is human. Discernment can help us move away from regarding ourselves as mistakes (Victim). By seeing our errors as human we can take responsibility for our part, correct what we can, and learn from the incident. In so doing, we move out of toxic guilt and a battle of wills.

- Name the dynamic: Perceiving the situation with awareness through the eyes of an observer, can move us away from ‘right vs. wrong’ and describe the dynamic that is unfolding. This can move us towards learning and connection.

- Separate the request from the person. Explain that you are saying ‘no’ to the request and not rejecting them as a person.

- Don’t go on their guilt trip! A true request is without demands, shame or guilt; it is voluntarily accepted or turned down with no negative consequences. Anything else is a power struggle.

- Look for a compromise: When we name our needs and regard them as equal to others, neither above nor below, we are able to be assertive in a mutually respectful manner.

Conclusion

Guilt can be both a healthy measure for our morals and an emotional poison. When we see guilt in all-or-nothing terms, we engage in its toxicity through the Drama Triangle. Here we either take on more than our part, or dodge taking responsibility.

However this simply takes us deeper into blame, resentment and power imbalances and further away from unmasking our vulnerability.

By seeing vulnerability as a shared aspect of our humanness, we can find a more compassionate middle ground and can let the curtain fall on this play.